Toolkit for the Monte Carlo and data analysis for the Digital Tracking Calorimeter project. For more details see the publication Pettersen, H. E. S. et al., Proton tracking in a high-granularity Digital Tracking Calorimeter for proton CT purposes. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research A 860 (C): 51 - 61 (2017) https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2017.02.007 and the PhD thesis A Digital Tracking Calorimeter for Proton Computed Tomography: University of Bergen 2018. http://bora.uib.no/handle/1956/17757

It is developed for the management, pre-processing, reconstruction, analysis and presentation of data from the beam test and from MC simulations. It is of a modular and object-oriented design, such that it should be simple to extend the software with the following purposes in mind: to include analysis data from multiple sources such as the next-generation readout electronics and different MC simulation software; to give the user a broad selection of different geometrical, physical and reconstruction models; to include a more extensive proton CT simulation with complex phantoms and positional trackers before and after the phantom or patient; and to facilitate further development and usage of the software by making it available as a analysis library.

The software is written in C++ and ROOT, with some auxiliary tools written in Python and user scripts written in bash. Several hands-on teaching workshops have been held at the University of Bergen in order to demonstrate the usage of the software, and summaries of these are available at the project documentation website https://wiki.uib.no/pct/. In total the framework with tools consists of approximately 20 000 lines of code.

- Generating GATE simulation files

- Perfoming GATE simulations

- Making range-energy tables, finding the straggling, etc.

- Tracking analysis: This can be done both simplified and full

- Simplified: No double-modelling of the pixel diffusion process (use MC provded energy loss), no track reconstruction (use eventID tag to connect tracks from same primary).

- The 3D reconstruction of phantoms using tracker planes has not yet been implemented

- Range estimation

The analysis toolchain has the following components:

The full tracking workflow is implemented in the function DTCToolkit/HelperFunctions/getTracks.C::getTracks(), and the tracking and range estimation workflow is found in DTCToolkit/Analysis/Analysis.C::drawBraggPeakGraphFit().

The simplified simulation geometry for the future DTC simulations has been proposed as:

It is partly based on the ALPIDE design, and the FoCal design. The GATE geometry corresponding to this scheme is based on the following hierarchy:

World -> Scanner1 -> Layer -> Module + Absorber + Air gap

Module = Active sensor + Passive sensor + Glue + PCB + Glue

-> Scanner2 -> [Layer] * Number Of Layers

The idea is that Scanner1 represents the first layer (where e.g. there is no absorber, only air), and that Scanner2 represents all the following (similar) layers which are repeated.

To generate the geometry files to run in Gate, a Python script is supplied. It is located within the ''gate/python'' subfolder.

[gate/python] $ python gate/python/makeGeometryDTC.py

Choose the wanted characteristics of the detector, and use ''write files'' in order to create the geometry file Module.mac, which is automatically included in Main.mac. Note that the option "Use water degrader phantom" should be checked (as is the default behavior)!

In this step, 5000-10000 particles are usually sufficient in order to get accurate results. To loop through different energy degrader thicknesses, run the script ''runDegraderFull.sh'':

[gate/python] $ ./runDegraderFull.sh <absorber thickness> <degraderthickness from> <degraderthickness stepsize> <degraderthickness to>

The brackets indicate the folder in the Github repository to run the code from. Please note that the program should not be executed using the sh command, as this refers do different shells in different Linux distribtions, and not all shells support the conditional bash expressions used in the script.

For example, with a 3 mm degrader, and simulating a 250 MeV beam passing through a phantom of 50, 55, 60, 65 and 70 mm water:

[gate/python] $ ./runDegraderFull.sh 3 50 5 70

Please note that there is a variable NCORES in this script, which ensures that NCORES versions of the Gate executable are run in parallel, and then waits for the last background process to complete before a new set of NCORES executables are run. So if you set NCORES=8, and run sh runDegraderFull.sh 3 50 1 70, first 50-57 will run in parallel, and when they're done, 58-65 will start, etc. The default value is NCORES=4.

In this step a higher number of particles is desired. I usually use 25000 since we need O(100) simulations. A sub 1-mm step size will really tell us if we manage to detect such small changes in a beam energy.

And loop through the different absorber thicknesses:

[gate/python] $ ./runDegrader.sh <absorber thickness> <degraderthickness from> <degraderthickness stepsize> <degraderthickness to>

The same parallel-in-sequential run mode has been configured here.

Now we have ROOT output files from Gate, all degraded differently through a varying water phantom and therefore stopping at different places in the DTC. We want to follow all the tracks to see where they end, and make a histogram over their stopping positions. This is of course performed from a looped script, but to give a small recipe:

- Retrieve the first interaction of the first particle. Note its event ID (history number) and edep (energy loss for that particular interaction)

- Repeat until the particle is outside the phantom. This can be found from the volume ID or the z position (the first interaction with {math|z>0}). Sum all the found edep values, and this is the energy loss inside the phantom. Now we have the "initial" energy of the proton before it hits the DTC

- Follow the particle, noting its z position. When the event ID changes, the next particle is followed, and save the last z position of where the proton stopped in a histogram

- Do a Gaussian fit of the histogram after all the particles have been followed. The mean value is the range of the beam with that particular "initial" energy. The spread is the range straggling. Note that the range straggling is more or less constant, but the contributions to the range straggling from the phantom and DTC, respectively, are varying linearly.

This recipe has been implemented in DTCToolkit/Scripts/findRange.C. Test run the code on a few of the cases (smallest and biggest phantom size ++) to see that

- The correct start- and end points of the histogram looks sane. If not, this can be corrected for by looking how

xfromandxtois calculated and playing with the calculation. - The mean value and straggling is calculated correctly

- The energy loss is calculated correctly

You can run

findRange.Cin root by compiling and giving it three arguments; Energy of the protons, absorber thickness, and the degrader thickness you wish to inspect.

[DTCToolkit/Scripts] $ root

ROOT [1] .L findRange.C+

// void findRange(Int_t energy, Int_t absorberThickness, Int_t degraderThickness)

ROOT [2] findRange f(250, 3, 50); f.Run();

The output should look like this: Correctly places Gaussian fits is a good sign.

If you're happy with this, then a new script will run findRange.C on all the different ROOT files generated earlier.

[DTCToolkit/Scripts] $ root

ROOT [1] .L findManyRangesDegrader.C

// void findManyRanges(Int_t degraderFrom, Int_t degraderIncrement, Int_t degraderTo, Int_t absorberThicknessMm)

ROOT [2] findManyRanges(50, 5, 70, 3)

This is a serial process, so don't worry about your CPU.

The output is stored in DTCToolkit/Output/findManyRangesDegrader.csv.

It is a good idea to look through this file, to check that the values are not very jumpy (Gaussian fits gone wrong).

We need the initial energy and range in ascending order. The findManyRangesDegrader.csv files contains more rows such as initial energy straggling and range straggling for other calcualations. This is a bit tricky, but do (assuming a 3 mm absorber geometry):

[DTCToolkit] $ cat OutputFiles/findManyRangesDegrader.csv | awk '{print ($6 " " $3)}' | sort -n > Data/Ranges/3mm_Al.csv

NB: If there are many different absorber geometries in findManyRangesDegrader, either copy the interesting ones or use | grep " X " | to only keep X mm geometry

When this is performed, the range-energy table for that particular geometry has been created, and is ready to use in the analysis. Note that since the calculation is based on cubic spline interpolations, it cannot extrapolate -- so have a larger span in the full Monte Carlo simulation data than with the chip readout. For more information about that process, see this document:

It is important to know the amount of range straggling in the detector, and the amount of energy straggling after the degrader. In addition, to calculate the parameters \alpha, p from the somewhat inaccurate Bragg-Kleeman equation R_0 = \alpha E ^ p, in order to correctly model the "depth-dose curve" dE / dz = p^{-1} \alpha^{-1/p} (R_0 - z)^{1/p-1}. This happens automatically in DTCToolkit/GlobalConstants/MaterialConstants.C, so there is no need to do this by hand. This step should be followed anyhow, since it is a check of the data produced in the last step: Outliers should be removed or "fixed", eg. by manually fitting the conflicting datapoints using findRange.C.

To find all this, run the script DTCToolkit/Scripts/findAPAndStraggling.C. This script will loop through all available data lines in the DTCToolkit/OutputFiles/findManyRangesDegrader.csv file that has the correct absorber thickness, so you need to clean the file first (or just delete it before running findManyRangesDegrader.C).

[DTCToolkit/Scripts] $ root

ROOT [0] .L findAPAndStraggling.C+

// void findAPAndStraggling(int absorberthickness)

ROOT [1] findAPAndStraggling(3)

The output from this function should be something like this:

The values from findManyRanges.C should already be in DTCToolkit/Data/Ranges/3mm_Al.csv (or the corresponding material / thickness).

Look in the file DTCToolkit/GlobalConstants/Constants.h and check that the correct absorber thickness values etc. are set:

...

39 Bool_t useDegrader = true;

...

52 const Float_t kAbsorberThickness = 3;

...

59 Int_t kEventsPerRun = 100000;

...

66 const Int_t kMaterial = kAluminum;

Since we don't use tracking but only MC truth in the optimization, the number kEventsPerRun (n_p in the NIMA article) should be higher than the number of primaries per energy. If tracking is to be performed anyhow, turn on the line

const kDoTracking = true;

The following section will detail how to perform these separate steps. A quick review of the classes available:

Hit: A (int x,int y,int layer, float edep) object from a pixel hit. edep information only from MCHits: ATClonesArraycollection of Hit objectsCluster: A (float x, float y, int layer, float clustersize) object from a cluster ofHits The (x,y) position is the mean position of all involved hits.Clusters: ATClonesArraycollection ofClusterobjects.Track: ATClonesArraycollection ofClusterobjects... But only one per layer, and is connected through a physical proton track. Many helpful member functions to calculate track properties.Tracks: ATClonesArraycollection ofTrackobjects.Layer: The contents of a single detector layer. Is stored as aTH2Fhistogram, and has aLayer::findHitsfunction to find hits, as well as the cluster diffusion modelLayer::diffuseLayer. It is controlled from aCalorimeterFrameobject.CalorimeterFrame: The collection of allLayers in the detector.DataInterface: The class to talk to DTC data, either through semi-Hitobjects as retrieved from Utrecht from the Groningen beam test, or from ROOT files as generated in Gate.

'''Important''': To load all the required files / your own code, include your C++ sources files in the DTCToolkit/Load.C file, after Analysis.C has loaded:

...

gROOT->LoadMacro("Analysis/Analysis.C+");

gROOT->LoadMacro("Analysis/YourFile.C+"); // Remember to add a + to compile your code

}

In the class DataInterface there are several functions to read data in ROOT format.

int getMCFrame(int runNumber, CalorimeterFrame *calorimeterFrameToFill, [..]) <- MC to 2D hit histograms

void getMCClusters(int runNumber, Clusters *clustersToFill); <-- MC directly to clusters w/edep and eventID

void getDataFrame(int runNumber, CalorimeterFrame *calorimeterFrameToFill, int energy); <- experimental data to 2D hit histograms

To e.g. obtain the experimental data, use

DataInterface *di = new DataInterface();

CalorimeterFrame *cf = new CalorimeterFrame();

for (int i=0; i<numberOfRuns; i++) { // One run is "readout + track reconstruction

di->getDataFrame(i, cf, energy);

// From here the object cf will contain one 2D hit histogram for each of the layers

// The number of events to readout in one run: kEventsPerRun (in GlobalConstants/Constants.h)

}

Examples of the usage of these functions are located in DTCToolkit/HelperFunctions/getTracks.C.

Please note the phenomenological difference between experimental data and MC:

- Exp. data has some noise, represented as "hot" pixels and 1-pixel clusters

- Exp. data has diffused, spread-out, clusters from physics processes

- Monte Carlo data has no such noise, and proton hits are represented as 1-pixel clusters (with edep information)

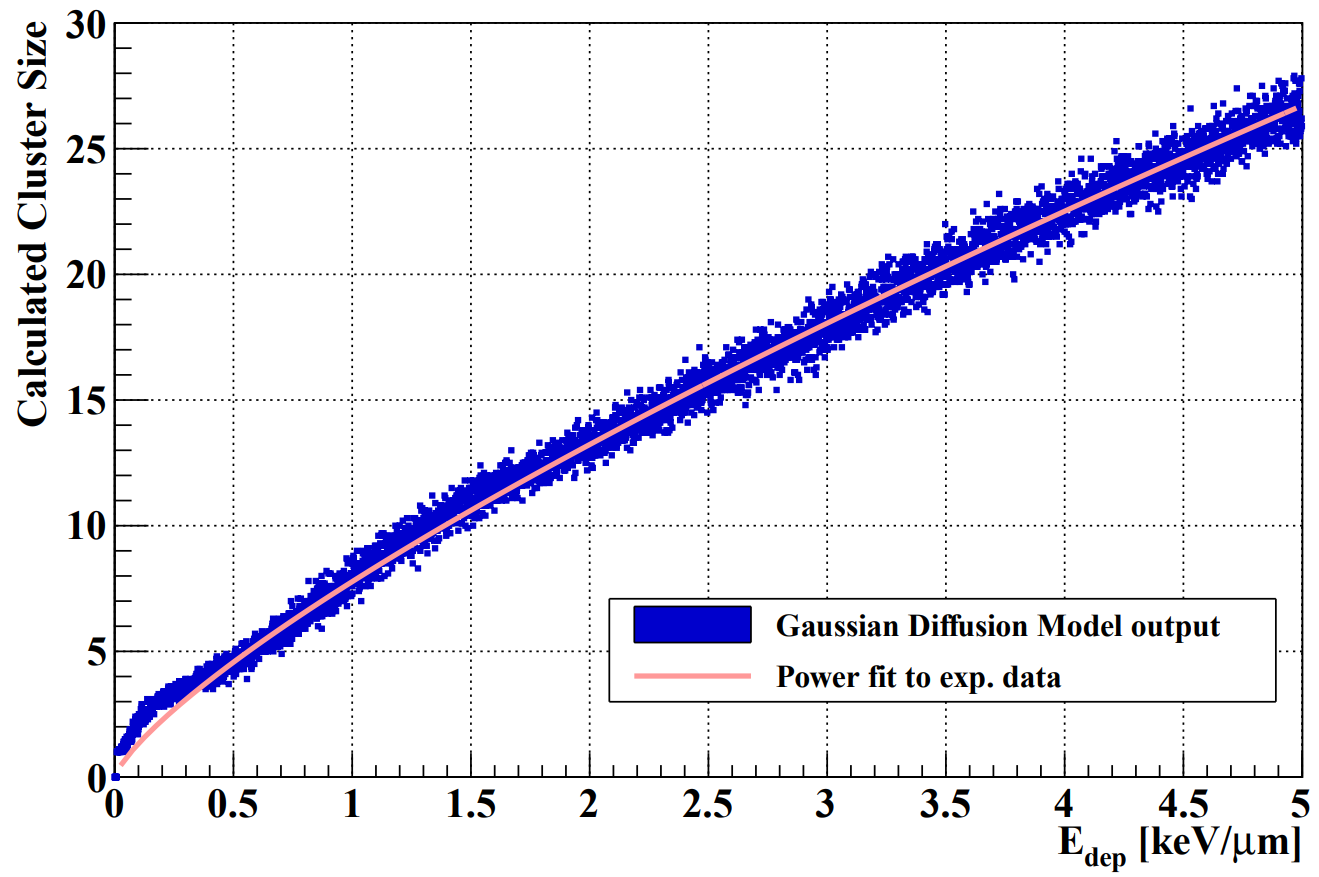

To model the pixel diffusion process, i.e. the the diffusion of the electron-hole pair charges generated from the proton track towards nearby pixels, an empirical model has been implemented. It is described in the NIMA article [[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2017.02.007]], and also in the source code in DTCToolkit/Classes/Layer/Layer.C::diffuseLayer.

To perform this operation on a filled CalorimeterFrame *cf, use

TRandom3 *gRandom = new TRandom3(0); // use #import <TRandom3.h>

cf->diffuseFrame(gRandom);

This process has been inversed in a Python script, and performed with a large number of input cluster sizes. The result is a parameterization between the proton's energy loss in a layer, and the number of activated pixels:

The function DTCToolkit/HelperFunctions/Tools.C::getEdepFromCS(n) contains the parameterization:

Float_t getEdepFromCS(Int_t cs) {

return -3.92 + 3.9 * cs - 0.0149 * pow(cs,2) + 0.00122 * pow(cs,3) - 1.4998e-5 * pow(cs,4);

}

Cluster identification is the process to find all connected hits (activated pixels) from a single proton in a single layer. It can be done by several algorithms, simple looped neighboring, DBSCAN, ... The process is such:

- All hits are found from the diffused 2D histograms and stored as

Hitobjects with (x,y,layer) in a TClonesArray list. - This list is indexed by layer number (a new list with the index the first Hit in each layer) to optimize any search

- The cluster finding algorithm is applied. For every Hit, the Hit list is looped through to find any connected hits. The search is optimized by use of another index list on the vertical position of the Hits. All connected hits (vertical, horizontal and diagonal) are collected in a single Cluster object with (x,y,layer,cluster size), where the cluster size is the number of its connected pixels.

This task is simply performed on a diffused CalorimeterFrame *cf:

Hits *hits = cf->findHits();

Clusters *clusters = hits->findClustersFromHits();

The process of track reconstruction is described fully in [[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2017.02.007]].

From a collection of cluster objects, Clusters * clusters, use the following code to get a collection of the Track objects connecting them across the layers.

Tracks * tracks = clusters->findCalorimeterTracks();

Some optimization schemes can be applied to the tracks in order to increase their accuracy:

tracks->extrapolateToLayer0(); // If a track was found starting from the second layer, we want to know the extrapolated vector in the first layer

tracks->splitSharedClusters(); // If two tracks meet at the same position in a layer, and they share a single cluster, split the cluster into two and give each part to each of the tracks

tracks->removeTracksLeavingDetector(); // If a track exits laterally from the detector before coming to a stop, remove it

tracks->removeTracksEndingInBadChannnels(); // ONLY EXP DATA: Use a mask containing all the bad chips to see if a track ends in there. Remove it if it does.

It is not easy to track a large number of proton histories simultaneously, so one may want to loop this analysis, appending the result (the tracks) to a larger Tracks list. This can be done with the code below:

DataInterface *di = new DataInterface();

CalorimeterFrame *cf = new CalorimeterFrame();

Tracks * allTracks = new Tracks();

for (int i=0; i<numberOfRuns; i++) { // One run is "readout + track reconstruction

di->getDataFrame(i, cf, energy);

TRandom3 *gRandom = new TRandom3(0); // use #import <TRandom3.h>

cf->diffuseFrame(gRandom);

Hits *hits = cf->findHits();

Clusters *clusters = hits->findClustersFromHits();

Tracks * tracks = clusters->findCalorimeterTracks();

tracks->extrapolateToLayer0();

tracks->splitSharedClusters();

tracks->removeTracksLeavingDetector();

tracks->removeTracksEndingInBadChannnels();

for (int j=0; j<tracks->GetEntriesFast(); j++) {

if (!tracks->At(j)) continue;

allTracks->appendTrack(tracks->At(j));

}

delete tracks;

delete hits;

delete clusters;

}

To obtain the most likely residual range / stopping range from a Track object, use

track->doRangeFit();

float residualRange = track->getFitParameterRange();

What happens here is that a TGraph with the ranges and in-layer energy losses of all the Cluster objects is constructed. A differentiated Bragg Curve is fitted to this TGraph:

f(z) = p^{-1} \alpha^{-1/p} (R_0 - z)^{1/p-1}

With p,\alpha being the parameters found during the full-scoring MC simulations. The value R_0, or track::getFitParameterRange is stored.

When the volume reconstruction is implemented, it is to be put here:

- Calculate the residual range and incoming vectors of all protons

- Find the Most Likely Path (MLP) of each proton

- Divide the proton's average energy loss along the MLP

- Then, with a measure of a number of energy loss values in each voxel, perform some kind of average scheme to find the best value.

Instead, we now treat the complete detector as a single unit / voxel, and find the best SUM of all energy loss values (translated into range). The average scheme used in this case is described below, however this might be different than the best one for the above case.

To calculate the most likely residual range from a collection of individual residual ranges is not a simple task! It depends on the average scheme, the distance between the layers, the range straggling etc. Different solutions have been attempted:

- In cases where the distance between the layers is large compared to the straggling, a histogram bin sum based on the depth of the first layer identified as containing a certain number of proton track endpoints is used. It is the method detailed in the NIMA article [[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2017.02.007]], and it is implemented in

DTCToolkit/Analysis/Analysis.C::doNGaussianFit(*histogram, *means, *sigmas). - In cases where the distance between the layers is small compared to the straggling, a single Gaussian function is fitted on top of all the proton track endpoints, and the histogram bin sum average value is calculated from minus 4 sigma to plus 4 sigma. This code is located in

DTCToolkit/Analysis/Analysis.C::doSimpleGaussianFit(*histogram, *means, *sigmas). This is the version used for the geometry optimization project.

With a histogram hRanges containing all the different proton track end points, use

float means[10] = {};

float sigmas[10] = {};

TF1 *gaussFit = doSimpleGaussianFit(hRanges, means, sigmas);

printf("The resulting range of the proton beam if %.2f +- %.2f mm.\n", means[9], sigmas[9]);

The resolution in this case is defined as the width of the final range histogram for all protons. The goal is to match the range straggling which manifests itself in the Gaussian distribution of the range of all protons in the DTC, from the full Monte Carlo simulations:

To characterize the resolution, a realistic analysis is performed. Instead of scoring the complete detector volume, including the massive energy absorbers, only the sensor chips placed at intervals (\Delta z = 0.375\ \textrm{mm} + d_{\textrm{absorber}}) are scored. Tracks are compiled by using the eventID tag from GATE, so that the track reconstruction efficiency is 100%. Each track is then put in a depth / edep graph, and a Bragg curve is fitted on the data:

The distribution of all fitted ranges (simple to calculate from fitted energy) should match the distribution above - with a perfect system. All degradations during analysis, sampling error, sparse sampling, mis-fitting etc. will ensure that the peak is broadened.

To find this resolution, or degradation in the straggling width, for a single energy, run the DTC toolkit analysis.

[DTCToolkit] $ root Load.C

// drawBraggPeakGraphFit(Int_t Runs, Int_t dataType = kMC, Bool_t recreate = 0, Float_t energy = 188, Float_t degraderThickness = 0)

ROOT [0] drawBraggPeakGraphFit(1, 0, 1, 250, 34)

This is a serial process, so don't worry about your CPU when analysing all ROOT files in one go. With the result

The following parameters are then stored in DTCToolkit/OutputFiles/results_makebraggpeakfit.csv:

| Absorber thickness | Degrader thickness | Nominal WEPL range | Calculated WEPL range | Nominal WEPL straggling | Calculated WEPL straggling |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 (mm) | 34 (mm) | 345 (mm WEPL) | 345.382 (mm WEPL) | 2.9 (mm WEPL) | 6.78 (mm WEPL) |

To perform the analysis on all different degrader thicknesses, use the script DTCToolkit/makeFitResultPlotsDegrader.sh (arguments: degrader from, degrader step and degrader to):

[DTCToolkit] $ sh makeFitResultsPlotsDegrader.sh 1 1 380

This may take a few minutes... When it's finished, it's important to look through the file results_makebraggpeakfit.csv to identify all problem energies, as this is a more complicated analysis than the range finder above. If any is identified, run the drawBraggPeakGraphFit at that specific degrader thickness to see where the problems are.

If there are no problems, use the script DTCToolkit/Scripts/makePlots.C to plot the contents of the file DTCToolkit/OutputFiles/results_makebraggpeakfit.csv:

[DTCToolkit/Scripts/optimization] $ root plotRangesAndStraggling.C

The output is a map of the accuracy of the range determination, and a comparison between the range resolution (#sigma of the range determination) and its lower limit, the range straggling.

To clone the project, run

git clone https://github.com/HelgeEgil/focal

in a new folder to contain the project. The folder structure will be

DTCToolkit/ <- the reconstruction and analysis code

DTCToolkit/Analysis <- User programs for running the code

DTCToolkit/Classes <- All the classes needed for the project

DTCToolkit/Data <- Data files: Range-energy look up tables, Monte Carlo code, LET data from experiments, the beam data from Groningen, ...

DTCToolkit/GlobalConstants <- Constants to adjust how the programs are run. Material parameters, geometry, ...

DTCToolkit/HelperFunctions <- Small programs to help running the code.

DTCToolkit/OutputFiles <- All output files (csv, jpg, ...) should be put here

DTCToolkit/RootFiles <- ROOT specific configuration files.

DTCToolkit/Scripts <- Independent scripts for helping the analysis. E.g. to create Range-energy look up tables from Monte Carlo data

gate/ <- All Gate-related files

gate/python <- The DTC geometry builder

projects/ <- Other projects related to WP1

The best way to learn how to use the code is to look at the user programs, e.g. Analysis.C::DrawBraggPeakGraphFit which is the function used to create the Bragg Peak model fits and beam range estimation used in the 2017 NIMA article. From here it is possible to follow what the code does. It is also a good idea to read through what the different classes are and how they interact:

Hit: A (int x,int y,int layer, float edep) object from a pixel hit. edep information only from MCHits: ATClonesArraycollection of Hit objectsCluster: A (float x, float y, int layer, float clustersize) object from a cluster ofHits The (x,y) position is the mean position of all involved hits.Clusters: ATClonesArraycollection ofClusterobjects.Track: ATClonesArraycollection ofClusterobjects... But only one per layer, and is connected through a physical proton track. Many helpful member functions to calculate track properties.Tracks: ATClonesArraycollection ofTrackobjects.Layer: The contents of a single detector layer. Is stored as aTH2Fhistogram, and has aLayer::findHitsfunction to find hits, as well as the cluster diffusion modelLayer::diffuseLayer. It is controlled from aCalorimeterFrameobject.CalorimeterFrame: The collection of allLayers in the detector.DataInterface: The class to talk to DTC data, either through semi-Hitobjects as retrieved from Utrecht from the Groningen beam test, or from ROOT files as generated in Gate.

To run the code, do

[DTCToolkit] $ root Load.C

and ROOT will run the script Load.C which loads all code and starts the interpreter. From here it is possible to directly run scripts as defined in the Analysis.C file:

ROOT [1] drawBraggPeakGraphFit(...)

- Making Monte Carlo data There are several GATE macros and bash scripts looping through these macros, located in gate/DTC/. • The Main_chip.mac and Main_full.mac files contain my most up-to-date detector geometry with a water box phantom in front. The chip file stores only hits on the ALPIDE slabs, while the full stores everything happening inside the detector for calibration purposes. • The Main_He_chip/full files are similar, but for helium In the Phantom subfolder we find the geometry for several phantoms + the most up-to-date detector geometry. These files are ordered such that Main[He]phantom.mac includes the .mac phantom files. Again the runRadiograph.sh and runCT.sh are bash scripts that loops through different variables, most importantly the spot scanning. (While this is possible through GateRTion this is a simple for loop for increased control of file output. Also, note that the Gate executable is run using tsp, which is the task spooler we’re using at the cluster.) The available phantoms are: • CTP404 phantom (sensitometry phantom) • Wedge phantom (for scanning the whole WEPL range in a single wedge-shaped phantom) • Headphantom (the pediatric head phantom) The MC data from the spot scanning is saved in git/DTCToolkit/Data/MonteCarlo. The naming is a bit ad hoc, but reflects the particle name, phantom name, rotation (e.g. for the head phantom) and spot position: • DTC_Final_Helium_headphantom_rotation90deg_spotx-014_spoty0020.root A single ROOT file is then made (due to simpler parallelization) with increasing eventID numbering such that: • For CT scans all spots are summed in a single scanning angle • For radiographs all Y spots are summed, yielding ~50 files in X direction This is done in combineSpots.C (CT) and combineSpotsRad.C (with versions for the different phantoms). This step is, sadly, manual as the file names have to be edited for each time. It’s not something I did too often to require further automatization. The end result for radiographs is, e.g., files such as DTC_Final_headphantom_rotation90deg_spotx-007_AllY.root

- Running the DTC Toolkit on the generated MC files

As you might know all the files are C++ but interpreted through ROOT. This made the workflow quite easy, and allowed for many different runnable functions (in Analysis/Analysis.C) without generating excutables for each.

The code is executed by:

• $ root Load.C

• ROOT >

Most of the workshow is controlled by the variables in GlobalConstants/Constants.h: particle type, energy, phantom / water degrader (see MC part above), phantom name, number of events per run, splitting of columns per rotation (True for Rad, False for CT; see combineSpots.C above) and many detector- and algorithm-specific flags. Some of the flags are legacy flags, such as kFinalDesign (always true), kOutputUnit (always WEPL), refined clustering (always true) +++.

The interface to the MC files is located in the file Classes/DataInterface/DataInterface.C. The pertinent function is DataInterface::getMCClustersThreshold. If the phantom type and name is specified in Constants.h, it should find the correct MC files if also the spot position is given.

This function takes an incrementing run number (eventID: runNumber * events per run), a Clusters* or Hits* object (depending if the output should be pixel hits or cluster positions w/MC true edep) and the spotX, spotY. It then performs a binary search (DataInterface::findSpotIndex) on the ROOT file to find the start index of the wanted spot position, and further searches for the wanted eventID number in that sublist of the ROOT file. When the correct entries are located, the values for layer (“baseID2 + level1ID – 2”) and x/y pixel number (“posX / dx + nx / 2”) and appends the found Hit to the Hits* list (which is a TClonesArray of Hit* objects).

The Hits* object is then given back to the function getTracksFromClusters in HelperFunctions/getTracks.C (which controls the logistics from ROOT to Tracks* objects). The Hits* is run through the diffuseHits functions that makes spread-out hits based on the cluster diffusion. Then diffusedHits->findClustersFromHits() are run, giving back the cluster objects with float x,y (center of gravity) + number of pixels / edep.

The next step (after some clean-up) is track reconstruction, through the function clusters->findTracksWithRecursiveWeighting() in Classes/Cluster/findTracks.C. If the data is properly fetched until this point, this process should run without any trouble.

Two further steps performed in getTrackFromClusters should be mentioned. A lot of filtering (NANs, empty tracks, tracks leaving detector, filling out of tracks leaving the detector) and other sanity checks are performed. Second, a list called CWT or ClustersWithoutTrack is made, for later visualization and calculation.

All this happens under the hood. For the user, what is necessary is to set the variables and run the loadOrCreateTracks() function from getTracks.C. This is usually done by a user script in Analysis.C. This file is very bloaty since it contains many functions with parameter scanning, filtering, visualization, output file generation and comparion between files.

When dealing with spot scanning, the simplest interface is to make a user script in Analysis.C with spotX, spotY as input variables. Then (for parallelization) a bash script runs through the vector of possible spotX values (all spotY in single file, remember):

for spotx in

seq -$xlim 7 $xlim; do root -l ‘Scripts/makeInputFileForImageReconstructionRad(‘$runs’, ‘$eventsPerRun’, ‘$rotationAngle’, ‘$spotx’, “’$1’”)’ (where $1 is the phantom name as argument to the bash script); done The Scripts/ file is then just a passthrough between ROOT and the full codebase to allow for arguments. One example from Analysis.C is a simple track depth-dose visualization script: